by Luciana Mellone

A few days ago, Pope Francis went on an apostolic visit to Korea and, for the first time in history, China allowed the papal aeroplane to fly over its national territory.

A few days ago, Pope Francis went on an apostolic visit to Korea and, for the first time in history, China allowed the papal aeroplane to fly over its national territory.

At first sight this would appear something normal but in fact it is not, because, as L’Osservatore Romano of 18 August observed: ‘The thoughts of the Supreme Pontiff go beyond the frontiers of the country that is hosting him. They reach those Asian countries with which the Holy See does not yet have full relations and call for that opening of dialogue which should benefit everyone. In Asia more than a half of the governments impose restrictions on liberty of religion and conscience. And there are those who show their anti-religious face as one of the distinctive elements of their identity. Francis implores bishops not to be discouraged and to continue to look for dialogue. But, to quote Benedict XVI, the Church does not engage in proselytism, it grows through attraction; it shows itself in all its identity so that everyone may see that it does not seek to conquer anybody. It proposes only a pathway to be followed side by side with each other’.

To think of Asia means to think of China and the fact that the papal aeroplane drew near, even metaphorically, to the People’s Republic of China is anyway an epochal episode that establishes to a certain extent the beginnings of an opening of the Asian giant not only to world markets but also to the possibility of spiritual exchanges with the Catholic Church.

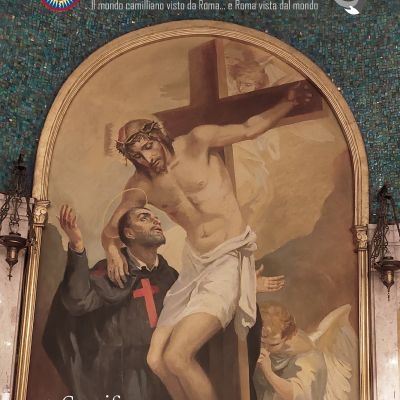

Relations between the Roman Church and the people’s Republic of China have never been idyllic and yet this region of the world, which is so populous, is a field of apostolate that is rich in opportunities but thick with obstacles, amidst populations linked to Buddhist spirituality, above all in places where abandonment and acute poverty are infinite; exploitation in work, modern slavery, and illnesses of various kinds, in particular leprosy, make an atrocious frame for a picture of so much abject poverty.

After a long voyage they reached the district of Hweitseh, in the north of Yunnan. That mountainous and wild province on the borders with Tibet, with few and difficult roads, which had remained outside the usual missionary routes of penetration. Arriving at Shanghai on 10 May, they began their long journey through the whole of China, from East to West, from Shanghai to Kunming and from Kunming to Zhaotongh, where, in all of the prefecture with a population of about three million inhabitants there existed just one hospital with fifty beds. The Camillian mission from that day onwards was a reality.

Very quickly the fruit of the assiduous and tenacious work of those apostles of charity made itself seen: the first Camillian house came into being (19 March 1947), the first stone of the St. Camillus Hospital was laid (20 July 1947), four clinics, a leper’s hospital with a hundred patients, an orphanage and much else besides. The local population who had seen these men with red crosses on their fronts arrive were at first incredulous faced with their altruism and charity which alleviated their suffering

and comforted their souls; very quickly they gathered around these foreigners without a face and without a name but with the single distinctive sign of redemption and truth. Even the most sceptical communists, xenophobes, felt disarmed by the charity, by the serenity of their Eucharistic services, when compared to their own rites. In a world of hatred, rancour, indifference and selfishness, the work of the Camillian missionaries with their love made a breach in the hearts of those suffering unhappy people. This was the great responsibility that the first missionaries who had arrived in that very far away and very different land: to help a suffering population.

This impassioned and fervent activity lasted for six years. The communists came to power in October 1949 and restrictions began for foreigners, as well as searches. Catholics were increasingly disorientated and throughout China a religious persecution was unleashed which also touched Yunnan, until the unhappy date of 17 April 1952 when the Camillian missionaries were expelled from the country and left behind them a large hospital which was used as a barracks by the revolutionary government, four clinics, two leper hospitals, three schools and an orphanage, but – and this was something that was even more painful – also two martyrs: Fr. Celestino Rizzi, the Superior of the mission, and Sister Claudia Martinelli of the women Ministers of the Sick.

Since then the mission has been divided into three branches: Thailand, Formosa and the Pescadores Islands.

After the removal of Br. Giordan, Fr. Matteo Kao took the situation in hand and now every two months goes on a tour to see how those lepers’ hospitals are administered and in some of them he has managed to entrust care for the sick to local sisters.

The pathway is long but the way pointed out by the Holy Father has already begun.